Think back to those fondly remembered halcyon days when you could sit in a dark room with other people and laugh out loud. Well those days just aren’t a happenin’ at the minute, but did you know that one of London’s largest and most vital cinemas used to exist in Kennington Cross?

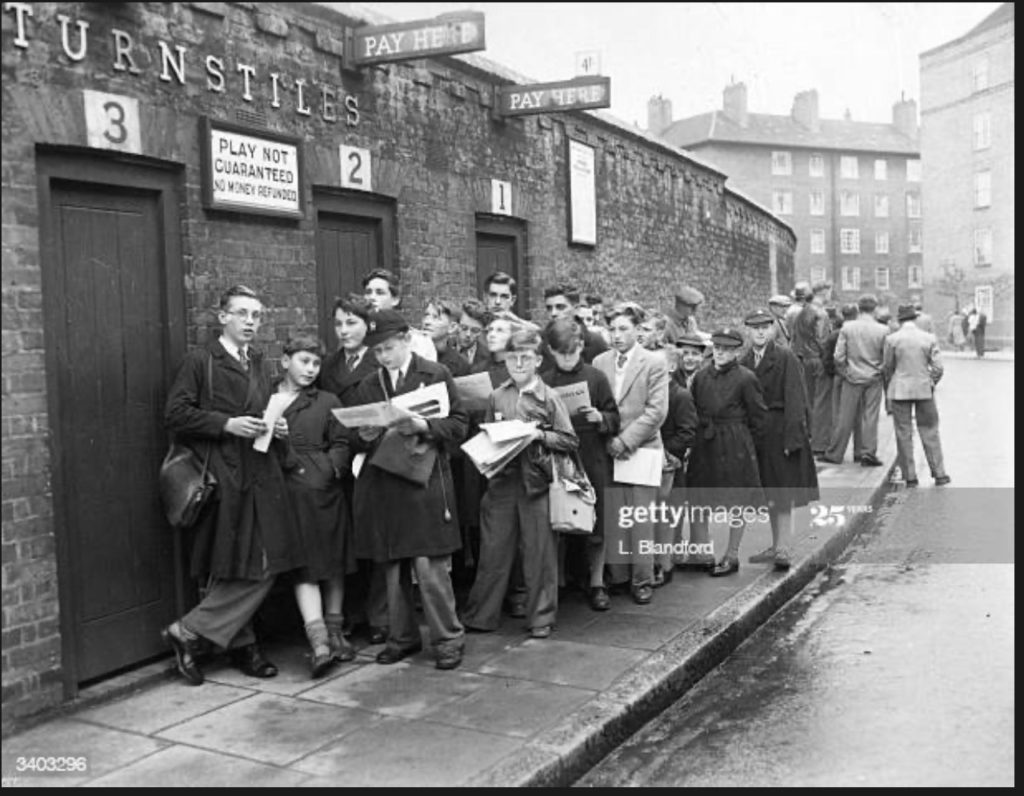

When the ‘Regal’ cinema opened in Kennington Road in 1937 it was advertised as ‘South London’s new luxury super cinema’. With 2100 seats, the cinema also had a large stage with dressing rooms behind the screen, creating its dual function as a theatre. The centrepiece was a spectacular 25 foot chandelier and full service cafe on the first floor.

The Regal survived the Blitz but by the late 1940’s it was suffering as a result of a rapid decline in cinema attendance (we suspect that the proximity to the West End didn’t help). Change was in the wind and it was sold to a larger chain and renamed the ‘Granada’ in 1948. Sadly even the Granada couldn’t make it work and our building was closed as a cinema forever in 1961.

There aren’t a whole lot of uses for a purpose built building with a massive stage and 2100 seats, but quickly Granada saw where the winds were prevailing – Bingo halls.Our Regal was called ‘Granada Club’ until 1991, when it was sold to Bass Holdings and renamed ‘Gala Bingo’. Some of you readers out there might have even tried your luck.

The decline of bingo halls in the late 90’s mirrored the decline of cinema 50 years previous, and the Regal was once again left adrift. And by the late 90’s the wind was in the direction of…. The mega church. Regal/Granada/Gala/Church was a place of evangelical worship for just five years until the mega church craze waned and gave way to the next wave….Property developers.

Regal/Granada/Gala/Church finally succumbed to the wrecking ball in 2004. Luckily, by then the building was part of a local conservation area, and Lambeth told the developers they could bulldoze some of the building but had to retain the original facade and entrance to the cinema. The entrance survives as part of our most recent wave of obsession….The mini supermarket. The rest of the site was redeveloped into what is now the architecturally soulless ‘Metro’ apartments, but inhabited by many lovely locals.